Stop hiring heroes. Start building engines.

In my years auditing value streams for organizations that look impressive on paper but are rotting from within, I’ve found that the most dangerous person in your company is the one who “knows where all the bodies are buried.” We celebrate these individuals. We give them bonuses and call them “top performers” or “domain experts.” In reality, they are systemic bottlenecks wrapped in a human skin. If your delivery pipeline stalls the moment a specific person takes a vacation or—God forbid—is headhunted by a competitor, you don’t have a business process. You have a hostage situation.

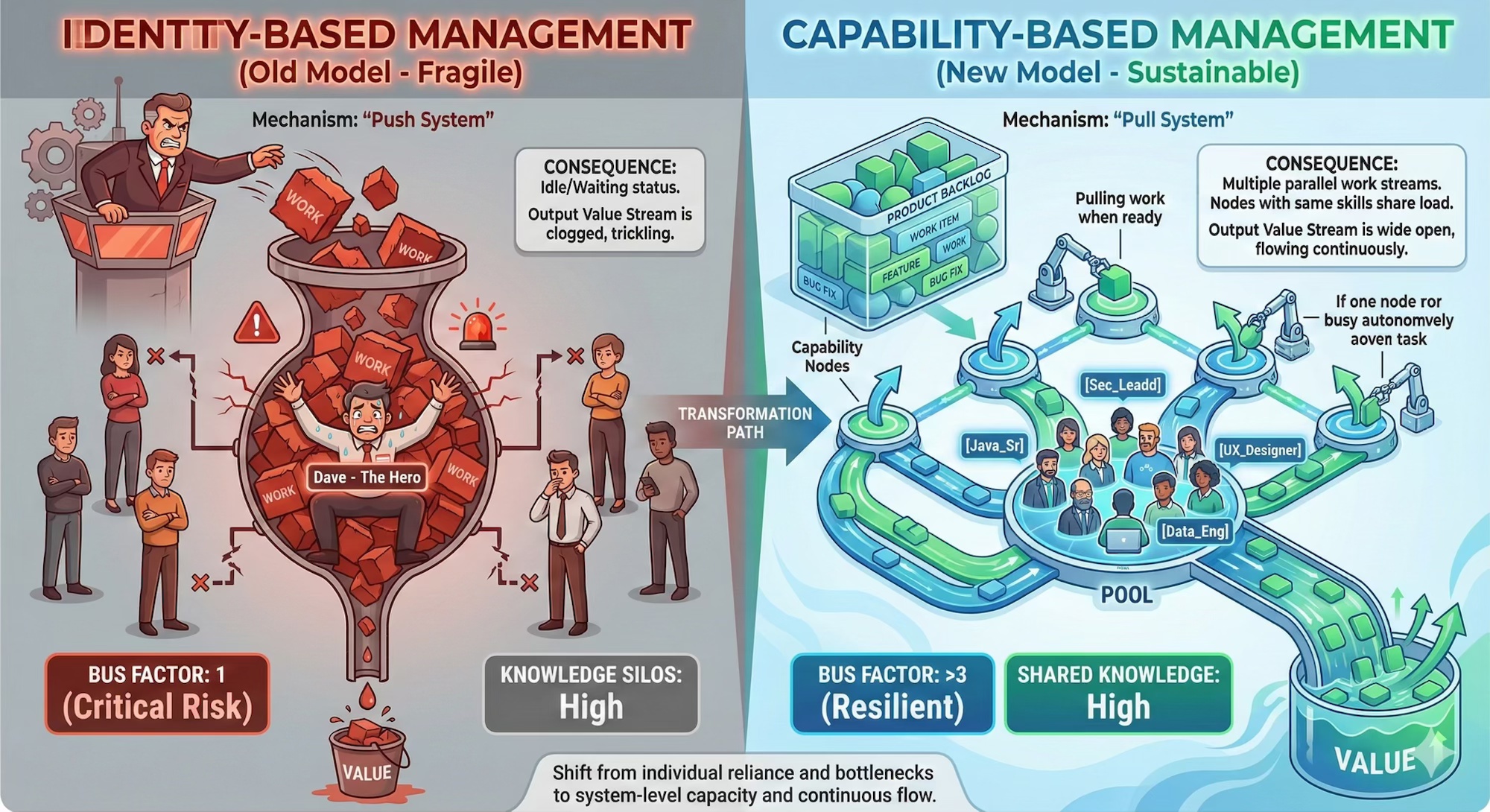

When we sit down to architect a workflow, the fatal error is focusing on “who” instead of “how.” Traditional management treats people as static assets to be assigned. This is a legacy of the industrial age that has no place in high-scale IT. Systems rarely fail for a lack of talent; they fail because the governance incentives knowledge hoarding. We audit delivery metrics like zealots while ignoring the toxic knowledge silos pulsing underneath. In a small squad or a midnight hotfix, assigning tasks by familiarity is a survival instinct. It’s pragmatic. But at scale, it is a massive Operational Risk that degrades the equity of the enterprise. It’s a habit that feels like efficiency but acts like a cancer.

The Myth of the Hero and the Reality of Architectural Debt

We have been conditioned to view the “Hero” as the pinnacle of engineering or operational excellence. This is a cognitive bias we must kill. As Gene Kim and his co-authors illustrated in The Phoenix Project, the character “Brent”—the guy who knows everything and is involved in every crisis—is actually the greatest threat to flow. Every time a “Hero” steps in to fix a module only they understand, they are not solving a problem. They are refinancing Technical Debt at a high interest rate.

From my own observations, I define this as “Architectural Debt”: the delta between your current system’s reliance on specific individuals and a theoretical state where any qualified node can execute any task within their capability set. When key tactical decisions rely on a single leader’s cognitive bandwidth, the Value Stream stalls. This is not elite performance; it is a structural flaw. We are leveraging human burnout to patch systemic gaps.

A Value Stream without self-organizing capabilities is inherently fragile. It cannot scale because its growth is capped by the biological limits of a few “key” people. If your “A-players” are constantly exhausted, it’s not because the work is hard. It’s because your system architecture is parasitic. It consumes the health of your best people to compensate for the lack of a repeatable process.

Shifting from Identity to “Units of Capability”

The solution isn’t better “people management.” It’s better system design. I prefer managing by Units of Capability rather than identity. This is a fundamental shift from a “Push” model—where a manager assigns a task to a person—to a “Pull” model, where the system presents work to qualified nodes.

To do this, we must implement a lightweight skill taxonomy. Think Java_Senior, Security_Lead, or FinOps_Architect. We stop seeing “John” and start seeing a “Node with Capability X, Y, and Z.” When work enters the backlog, it is tagged with the required capability units. Qualified nodes then pull work based on their current capacity.

This isn’t just about Jira labels or manual data entry—which I despise. It’s about decoupling the work from the face. As Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais argue in Team Topologies, reducing cognitive load is the key to organizational flow. By defining work through capability requirements, we remove the “familiarity bias” that keeps the same three people doing 80% of the critical tasks. Meanwhile, the rest of the team handles the “easy” stuff, never growing, never learning, and eventually, leaving. You end up with a team of one hero and nine observers. That is a recipe for disaster.

The Signal in the Stalling

What happens when a critical item sits in the backlog, unassigned, because no one has the required “Unit of Capability” tag? In most organizations, this is a crisis managed by shouting or “all-hands” meetings. In a properly architected system, this is a high-fidelity data signal.

An unassigned task is a diagnostic tool. It has exposed a Skill Gap in real-time. Instead of reacting with a manager’s whim, this signal should trigger a standardized triage process:

- Train: Do we pair the “Hero” with a “Novice” to transfer the capability right now?

- Reassign: Do we move capacity from a lower-priority value stream?

- Decompose: Can the task be broken down into simpler capability units that more people can handle?

- Escalate: Is this a strategic deficit that requires external hiring or a pivot in technology?

We act on data, not on anxiety. This approach treats the organization like a distributed computing network. If a packet cannot be processed, the network protocol identifies why and adjusts the routing or scales the resources. This is the essence of Value Stream Management, as explored in Mik Kersten’s Project to Product. You cannot manage what you do not measure, and you cannot measure what is hidden behind “John’s” expertise.

The Insurance Premium of Systemic Resilience

Transitioning to a capability-based pull system is not free. It requires a calculated throughput drop. You must intentionally slow down today to invest in pairing and knowledge transfer. I’ve seen VPs recoil at the thought of their “top dev” spending four hours a day teaching others instead of coding. They view this as waste.

I view it as an insurance premium. You are paying to kill personal dependency. You are buying systemic resilience. The ROI of knowledge transfer is not found in next week’s velocity; it is found in the “Bus Factor”—the number of people who can be hit by a bus before your project fails.

In a traditional “Hero” setup, your Bus Factor is 1. In a Capability-Unit architecture, you aim for 3 or higher across every critical module. ROI should be measured over a 6–12 month horizon. You will see a stabilization of Cycle Time and a dramatic reduction in Mean Time to Recovery (MTTR). The variability of your delivery—the “chaos” that executives hate—begins to smooth out into a predictable flow.

Architecting for the “Pull” Economy

Traditional “Push” management is a relic of industrial assembly lines. In the modern knowledge economy, the “Push” model creates massive queues and resentment. According to Donella Meadows in Thinking in Systems, one of the most effective leverage points in a system is the “structure of information flows.” By moving to a Pull model based on Capability Units, you are re-wiring the information flow of your company.

| Feature | Identity-Based (Push) | Capability-Based (Pull) |

|---|---|---|

| Assignment Logic | Managerial Intuition / “Who do I trust?” | Systemic Matching / “Who is capable?” |

| Primary Metric | Individual Utilization (%) | Flow Velocity & Throughput |

| Risk Profile | High (Single Points of Failure) | Low (Distributed Capability) |

| Knowledge | Hoarded (as Job Security) | Shared (as Systemic Health) |

| Scalability | Linear (Limited by Heroes) | Exponential (Limited by System) |

If you are a Director or a VP, your job is not to ensure John finishes his task. Your job is to ensure the system is capable of finishing the task regardless of whether John is there. This requires a ruthless intolerance for manual work and stale information. Your Capability Matrix must be a living data set, integrated into your workflow tools, providing a real-time heat map of where your organization is strong and where it is brittle.

From Speed to Anti-Fragility

A system’s maturity isn’t measured by how fast it runs with its key members, but by how long it thrives without them. If the flow stalls the moment those members step away, it isn’t a scalable architecture. It’s a bottleneck disguised as a person.

Nassim Taleb’s concept of Antifragility is the ultimate goal here. A fragile system breaks under stress. A resilient system resists stress. An antifragile system gets better under stress. When you treat unassigned tasks as signals to train and evolve, your organization becomes antifragile. Every gap exposed is an opportunity to strengthen the web of capabilities.

We must stop rewarding the “Firefighter.” The Firefighter is usually the one who left the matches lying around in the first place by failing to document, failing to mentor, and failing to automate. Instead, reward the “Architect”—the person who builds a system so robust that fires don’t start, or if they do, anyone on the team has the capability to extinguish them.

This transition requires courage. It requires telling your stakeholders that “Yes, we are slowing down this sprint to ensure that four people understand the payment gateway instead of just one.” It’s an uncomfortable conversation, but it’s the only one that leads to a sustainable, high-leverage organization.

The goal of a Value Stream Architect is to build a machine that works while they sleep. If you are still the one answering emails at 2 AM to solve a technical blocker, you haven’t built a machine. You’ve just built yourself a very expensive, high-stress cage. Kill the hero. Save the system.

Discover more from HogoFlow

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.